So, here you are. How’d that happen? Did a little bird send you? A Philosophy of Enjoyment? You’re kidding, right? Sounds like an excuse to misbehave (think salacious and audacious), but then, maybe you are depressed or anxious or flummoxed by existence or know someone who is, so you did a Google search looking for answers and stumbled upon a Philosophy of Enjoyment.

What? It happens.

Maybe, if you are receptive to what is presented by a relative far, far removed (meaning, yours truly, there’s no ChatGPT here), you’ll take it to heart, learn from it, laugh a bit and change your philosophy of life completely.

What? It happens.

Think about it: With 1.13 billion websites on the internet in 2023—82% of which are inactive—(source: Forbes Advisor), finding this site is like being hit by lightning.

And we all know how fun that is.

A Philosophy of Enjoyment addresses one problem: How does a person—like you and yours truly, for example, a person with a particular vantage point, with feelings, abilities, limitations and opinions; a person with an economic standing, living in multiple cultures, framed in a body, identifying with a gender or agender—how does such a person transcend, as in, go beyond or rise above a localized low-to-the-ground subjective perspective that’s possibly defective, addictive, depressive, sad, mad, or morose, so as to enjoy being alive and thinking to experience beauty, tranquility, sublimity and jocularity daily?

Moreover, how can a person transcend habituated thinking and what does transcendence have to do with enjoying a good life in a world rife with bedbugs? How does a person subjected to the unwelcome and unpleasant vicissitudes of life learn to see the world as beautiful and enjoyable with gratitude, without needing alcohol, edibles or anything? Is that even possible?

Of course it is. Transformation happens every day at sunrise. A new day, a new you. You decide who you’ll be and what you’ll do.

Cue music (to set the mood for transcendence and transformation):

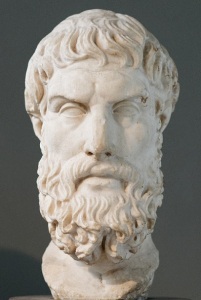

Ancient Greek philosophers like Aristotle, Epicurus and Epictetus emphasized eudaimonia. That’s an old word without a modern equivalent. Maybe that’s because eudaimonia encourages virtues like prudence and moderation, both of which may be considered old-fashioned bummers.

Eudaimonia is a Greek word commonly translated as happiness or welfare but it literally means the state or condition of good spirit, as in, eu = good and daimonia = spirit.

But the word spirit causes people to think of ghosts and disembodied astral projections when what we’re really talking about is a feeling.

Epicurus (341-270 BCE) set up a school in his garden to study what makes people happy. After years of study he found that happiness requires tranquility, freedom from fear, absence of pain, friendship and connection.

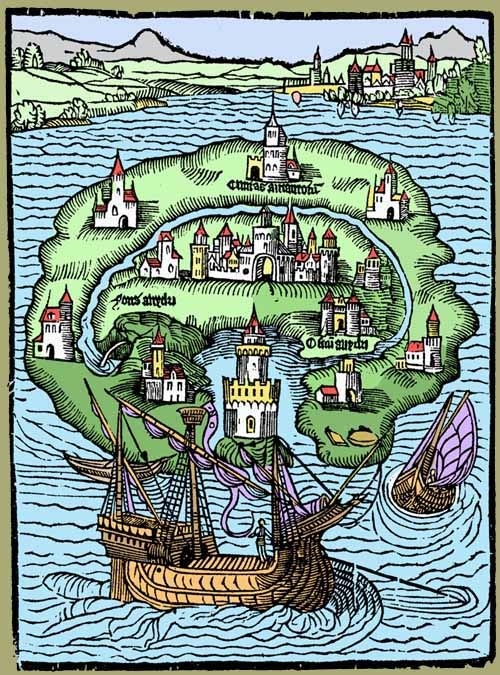

Incidentally, the word paradise comes from a Persian word which means Walled Garden. “The notion of Paradise as a garden predates Islam, Judaism, Christianity and even the Garden of Eden. It stems from the Sumerian period 4000BC in Mesopotamia. Shade and water are two important elements of paradise” (The Beauty and Paradise of Gardens).

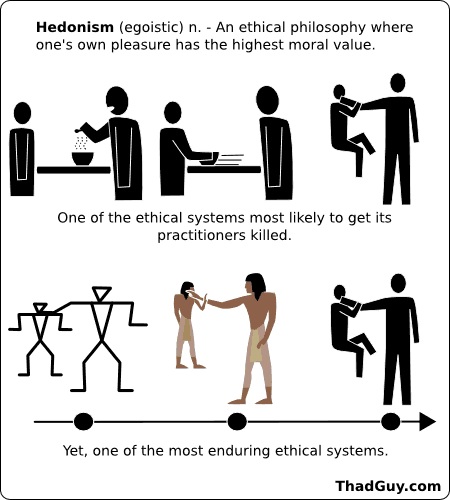

“Epicurus advocated living in such a way as to derive the greatest amount of pleasure possible during one’s lifetime, yet doing so moderately in order to avoid the suffering incurred by overindulgence in such pleasure” (Wikipedia).

It’s unfortunate, however, that pleasure is viewed with suspicion because it’s the excuse used for bad behaviour by the likes of sexual predators, traffickers and rude scoff-laws in loud cars who are all about their personal pleasure at the expense of others.

Epicurus wrote, “It is impossible to live a pleasant life without living wisely and well and justly. And it is impossible to live wisely and well and justly without living a pleasant life” (Classical Wisdom).

When a pleasure takes hold, however, if one isn’t careful, one may want more and more. Those who are addicted to a pleasure may no longer be willing participants. Sometimes we all think it would be nice if things were different. We might wish our self to be different. Those without religious affiliation might even wish there was more to life than a scientific explanation.

The philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677) said that God is nature, and, as you may have heard, psychological studies show, “People who are more connected with nature are happier, feel more vital, and have more meaning in their lives” (see: “How Modern Life Became Disconnected From Nature“, The Greater Good Magazine).

Philosopher Jonathan Rée (born 1948) said that Spinoza advised us to, “look with an attitude of love and reverence on the natural world as a whole and perhaps even yourself as a part of it… insofar as we’re irrational we’re divided, insofar as we’re rational we are united… freedom is not a matter of getting what you like. Freedom is learning to like what is rational to like” (Spinoza’s Ethics).

Happiness is in our nature (Springer Link). We just might not see it. We probably did as kids, but maybe not anymore (see also: Breathe in the air (and enjoy)). Happiness is available no matter who you are or what the situation. It takes a way of thinking that’s optimistic and a heart that is open without needing surgery.

Unless you are very young, you’ve probably realized that by living, time passes, and what’s happening now will become a mental movie which may or may not have occurred as remembered. The band OK Go put it this way: “… You know you can’t keep lettin’ it get you down, And you can’t keep draggin’ that dead weight around. If there ain’t all that much to lug around, Better run like hell when you hit the ground… When the morning comes” (“This Too Shall Pass”, 2010).

This is the end. Look at all angles and both ways too! March on. Think rational and love the world you’re in to make it even better (see also: Knowledge, Wisdom, Insight and Enjoyment).

Enjoy it. It’s for you.